Stop 4 - 5 Simple Steps to Learning to Read Music

In a previous stop we looked at some of the reasons why learning to read music can be useful for new guitar players. In this stop we will outline 5 Simple Steps to help you achieve that goal.

Step 1: Learn how Notes are represented on the staff

"Notes" are to the language of music like words are to spoken languages like English. We string a series of notes together into musical phrases and melodies to form what we normally call "songs".

The first basic property of all musical notes is its pitch.

Pitch is the up or down-ness of the note - how high or low it sounds. It is difficult to put into words, but just about everybody in our culture instinctively understands what this means.

As you probably already know, this is represented in written music by placing the note higher or lower on the musical staff.

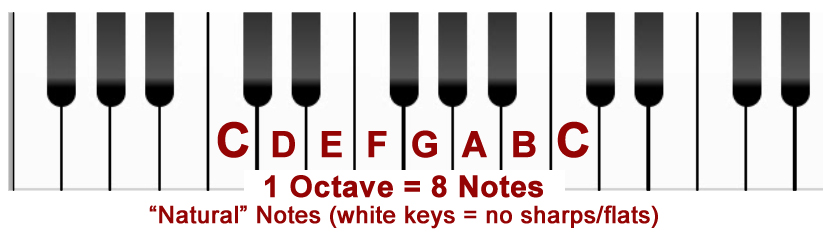

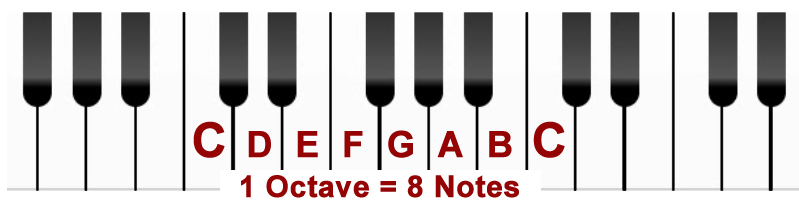

In music an octave is the range between two notes that sound the same, one lower and the other an octave higher. If you look at the piano keyboard you can see the same pattern of notes repeated several times. That is because notes having the same pitch - only higher or lower - are repeated in a regular sequence.

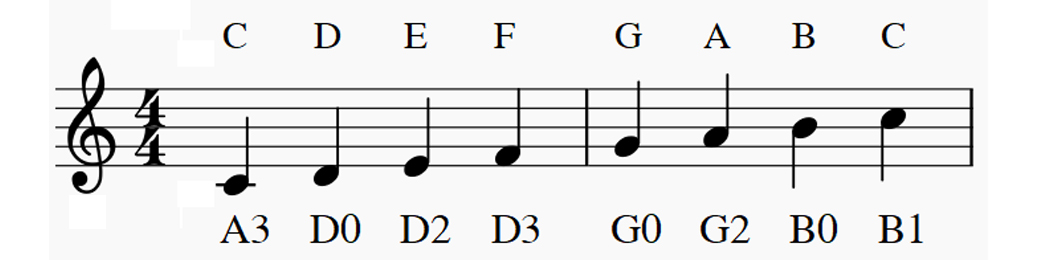

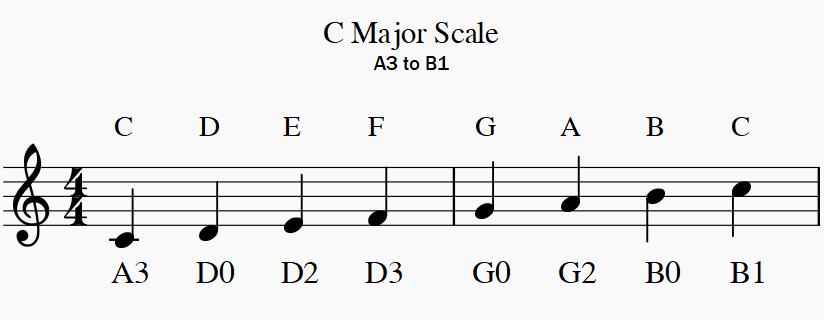

On the guitar there are two instances of the note C within the normal playing range of a beginner. The lower one is at the third fret of the A string (string 5) - which we refer to as A3. The higher one - an octave higher - is at the first fret of the B string (string 2), which we will refer to as B1.

When we write it in traditional musical notation A3 is one line below the staff. B1 is in the space between lines 3 and 4.

Now if you add the other notes in the C Major Scale between these two instances of C, they look like this: D is at the first space below the staff. E is at the first line of the staff. F is at space 1. G is at line 2. A is at space 2. And B is at line 3. That is how you write the C major scale.

One of the first things a new musician (guitarist, pianist, trumpeter, etc.) has to do is learn to relate the note positions on the staff to the technique for playing that note on the instrument. In the case of the pianist, the specific key; for the trumpet or saxophone player, the appropriate key or valve combination; for the guitar player, the unique position on the fretboard (which string, which fret).

For the guitar player this is not an easy task, since there are so many string/fret combinations. It does not happen quickly or all at once. It is a gradual process. But even at the most initial, elementary stages the process results in greater understanding and mastery of the instrument.

Step 2: Learn how Tempo and Note Length are represented on the staff

Tempo, Time Signature and Note Values

The second property of musical notes that is captured in written notation is the duration or length of individual notes - how long we "hold" a note before moving on to the next one.

This idea is closely related to "tempo" - how fast or slow a song is played. Tempo is speed at which "beats" move through the song. It is a measure of the temporal length of a beat.

If you tap your foot at a consistent rate of, say, 60 taps per minute (once every second), that would be called a tempo of 60 bpm (beats per minute). If you speed up your tapping to, say, 90 taps per minute, you would be increasing the tempo to 90 bpm.

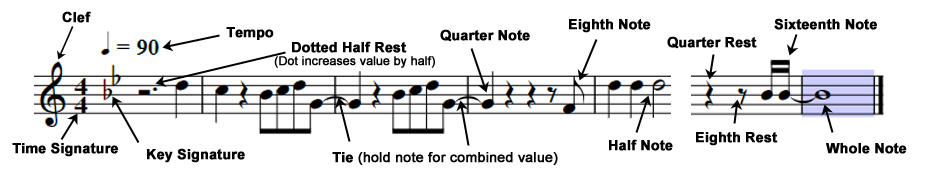

When a note is to be held for one beat it is indicated on the staff as a quarter note.

It is called a quarter note because, for the sake of convenience, music is divided into what are called "measures" (or "bars"). Each measure is essentially a short chunk of music containing a set number of beats. The simplest and most common measure contains 4 beats.

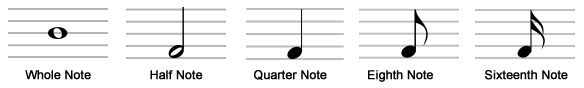

A note that is held for the entire measure (usually 4 beats) is called a whole note. A note held for half a measure is called a half note. And, as we've seen, a note held for a quarter of a measure - one standard "beat" - is called a quarter note*.

On the staff a whole note is signified by a hollow oval with no stem, and a half note by a hollow oval with a stem.

A quarter note is one beat* long, and it is signified on the staff by a solid oval shaped note with a stem. This can be divided into two eighth notes or four sixteenth notes.

An eighth note is signified on the staff as a quarter note with a flag. The sixteenth note has two flags.

These can be further divided into even shorter note durations: 32nds and 64ths. But for all practical purposes the longest note a beginning musician needs to be concerned with is a whole note, and the shortest is a 16th note.

Many musical compositions are written in what is called 4/4 time - where each measure contains 4 quarter notes. The 4/4 you see at the beginning of each staff is called a "time signature".

While 4/4 time is the most common (and, in fact, is called "common time"), it is not the only one found in music. For instance, a "waltz" is written is 3/4 time (3 quarter notes per measure).

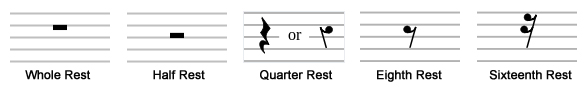

Rests - where you don't play anything

The other important element of written music is the rest. A rest indicates when you don't play a note. It is "dead air space".

Each note value (whole, half, quarter, eighth, sixteenth) has a comparable rest. They are signified on the staff as in the following graphic:

*This is technically not correct. As Widipedia says, "Often, musicians will say that a crotchet [quarter note] is one beat, but this is not always correct, as the beat is indicated by the time signature of the music; a quarter note may or may not be the beat." For practical purposes the beginner can ignore this technicality.

Step 3: Learn about sharps and flats, how Keys work

You are probably a bit familiar with the concept of musical "keys". This can be a complicated and confusing topic, so let me try to explain in as few words as I can, how the musical staff simplifies the matter.

For most of us specifying a musical "key" is simply a way of making clear:

(i) The pitch range the music is set in (the highest and lowest notes in the song), and

(ii) Which notes should be played as sharps, flats or "naturals".

Now let me unpack this. First, step back for a minute and think about how a typical "major scale" is constructed. It starts on Note 1 (the "root) and moves "up" in pitch a series of steps until it comes to Note 8 which is an octave higher than the root.

This movement up the major scale can be seen on the piano keyboard. If you start on C and play successive white notes you will come to C again, eight notes higher. These white notes represent what are called "natural notes" - C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C.

This is where it starts to get confusing

The piano keyboard also shows us that some notes of the C scale have a black key between them. So, for example, there is a black key between C and D. What this tells us is that there is actually another note between the natural tones C and D. We call that note C# or Db**.

This happens because in the tradition of western (European) music, the smallest gap in pitch between successive musical sounds is called a "semi-tone", or half a tone. The piano keyboard shows us that the gap between C and D is actually a full tone, and that there is another note a half tone above C, namely C#.

In fact, if we look at the piano keyboard closely we can see that some natural notes (white keys) have a black key between them, and some don't. This is another way of saying that some natural notes are only separated by a semi-tone.

There are only two instances of this: E to F and B to C. These two gaps are only a semi-tone, or what is often called a "half-step". All the other natural notes are separated by a full tone or "full step".

The major scale pattern - W-W-H-W-W-W-H

What emerges from this is that there is a pattern to the way a major scale works. Some notes are separated by an intermediate note (black key) and some are not. In this sense it is irregular. The pattern goes like this: whole step (C-D), whole step (D-E), half step (E-F), whole step (F-G), whole step (G-A), whole step (A-B), half step (B-C).

Now you're probably wondering how this is relevant to the idea of musical keys. Well, it is fairly simple.

When we say "This song is in the key of F", for example, what we are actually saying is "Play the song so that the anchor note or root note is F".

In other words, think of a song as a sequence of notes anchored at a particular place that gives it a particular pitch range. If the anchor point is C we will play (or sing) one set of notes. But if we move the anchor point up to D or E or G, the set of notes will be different.

The gaps between the notes will be the same but because of the irregularity of the whole-step/half-step pattern, the non-natural notes (sharps or flats) will fall in different places.

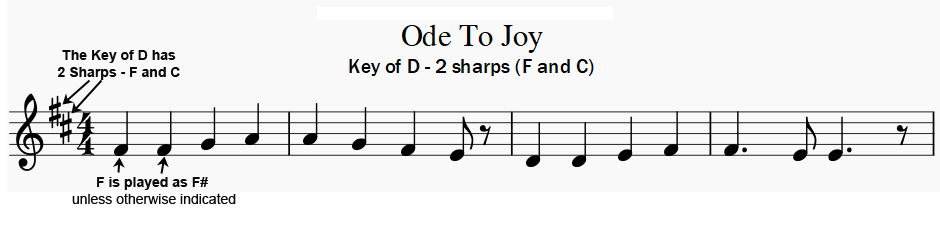

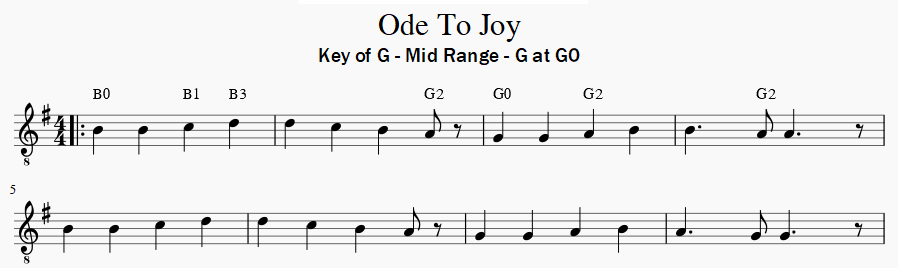

Just to take a fairly simple example, the song "Ode to Joy" starts out: (where the number is the note of the major scale): 3-3-4-5-5-4-3-2. In the key of C this would be E-E-F-G-G-F-E-D, but in the key of D it would be F#-F#-G-A-A-G-F#-E.

How the musical staff helps simplify this

What the staff allows us to do is to indicate that we are playing in a "key" where certain notes are to be played sharp or flat all the time (unless otherwise indicated).

If, for example, our anchor point is C (that is, if the song is played in the key of C) all the notes of the song will be natural (no sharps or flats) unless otherwise indicated.

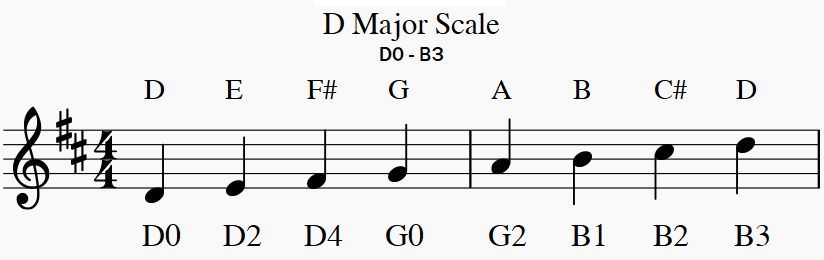

And, more importantly, if the anchor point of the song is D (that is, if the song is played in the key of D), the sequence of notes used in the song will include F sharp and C sharp. Everytime we see one of these notes on the staff we know to play them as sharps. All the other notes are natural (unless otherwise indicated).

The use of the staff allows us to put the complicated musical theory aside and just focus on playing the correct notes.

*To keep it simple, C# and Db are the same note - the note between C and D. When we're thinking in terms of sharps - e.g., in the key of D - we think of this note as C#. But when we're thinking in terms of flats - e.g., in the key of Gb - we think of this note as Db. Yes it is confusing, but hang in there.

Step 4: Start playing Major Scales from written music

It sounds over-simplified, but once you understand the bare basics, "learning to read" is just a matter of practice, practice, practice. The more you practice with written music, the more familiar you will become with it, and the more you will understand how it can help your guitar playing.

For a description of some practice tips, check out things to do before beginning serious work on scales and songs.

These things include:

- Learn the Names of the Strings

- Use correct Fingering Technique

- Use correct Picking Technique

Most new guitar players will begin with the C Scale because it has no sharps or flats and has you going from A3 up to B1 (and another octave up to E8).

Here is a simple exercise for the C Major Scale starting at A3. Here is one of the C Major Scale going from B1 to E8 (high E 8)..

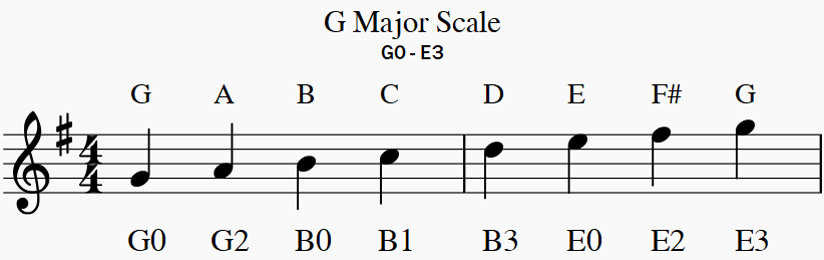

Two more relatively easy scales, and commonly used in songs are G and D...

Here is a scale exercise for G Major, and one for the G scale starting at low E3.

Another very popular key is D. Here is a D Major Scale Exercise starting at D0.

Step 5: Play Simple Melodies from written music

Now that you have a feel for how the staff works, and have familiarized yourself with some basic scales, it's time to try a few simple melodies.

I'm not talking about chording here. You'll get to do that soon enough (and no doubt are already doing it). What we're talking about is playing some simple songs from the written music.

This is different than playing "by ear". That's an extremely valuable skill to have too. But right here, right now, we want to learn how to play from the written music.

So, like most other beginning guitar players you'll want to start with some fairly simple melodies. The one that many people seem to learn is Ode to Joy. It's particularly easy because it goes up and down the scale in a very familiar way.

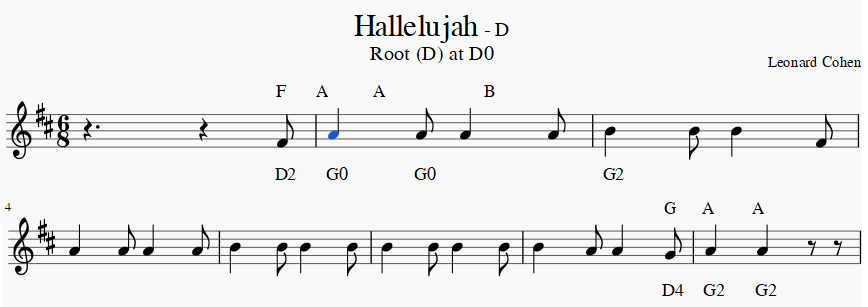

Some other easy melodies are Amazing Grace and the Leonard Cohen classic Hallelujah

These songs for beginning guitar players include the name of the note when it first appears, and how it is fingered.

Of course there are always nursery rhymes like Twinkle, Twinkle, and well-known patriotic and classic western songs (Home on the Range).

Christmas songs like Silent Night and Jingle Bells are also easy and very familiar.

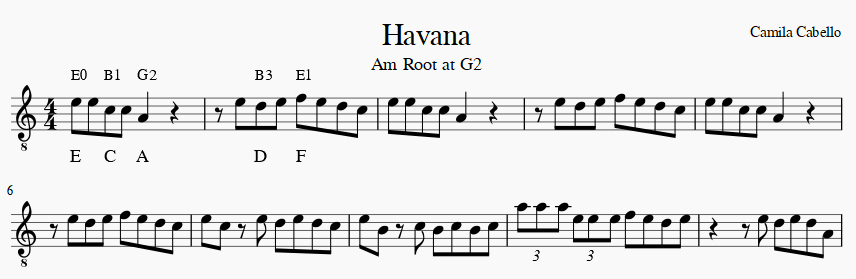

Many familiar popular songs are also surprisingly simple. Like the songs Budapest and Havana, for example.

The fact is, with resources like our Level 1 exercises and songs for new guitar players, you should be "reading" like a pro in no time!

Have fun!